-

Injury keeping you out of the game?Our experts will get to the core of your fitness needs.OUR SERVICES

Injury keeping you out of the game?Our experts will get to the core of your fitness needs.OUR SERVICES -

GET BACK TO THE ACTIVITIES YOU LOVEOUR SERVICES

GET BACK TO THE ACTIVITIES YOU LOVEOUR SERVICES -

RESTORING YOUR PHYSICAL ABILITYOUR SERVICES

RESTORING YOUR PHYSICAL ABILITYOUR SERVICES -

RESTORING YOUR QUALITY OF LIFEOUR SERVICES

RESTORING YOUR QUALITY OF LIFEOUR SERVICES -

EVIDENCE BASED PRACTICEOUR SERVICES

EVIDENCE BASED PRACTICEOUR SERVICES -

APPROPRIATE PROGRAM FOR A SUCCESSFUL RECOVERYOUR SERVICES

APPROPRIATE PROGRAM FOR A SUCCESSFUL RECOVERYOUR SERVICES -

HELPING YOU ACHIEVE YOUR GOALSOUR SERVICES

HELPING YOU ACHIEVE YOUR GOALSOUR SERVICES

Shoulder

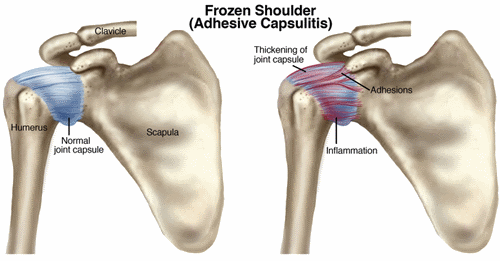

Frozen Shoulder (Adhesive Capsulitis)

Often called a stiff or “frozen shoulder,” adhesive capsulitis occurs in about 2% to 5% of the general population. It affects women more than men and typically occurs in people who are over the age of 45. Of the people who have had adhesive capsulitis in one shoulder, 20% to 30% will get it in the other shoulder

What is Frozen Shoulder (Adhesive Capsulitis)?

Adhesive capsulitis is the stiffening of the shoulder due to scar tissue, which results in painful movement and loss of motion.

The actual cause of adhesive capsulitis is a matter for debate. Some believe it is caused by inflammation, such as when the lining of a joint becomes inflamed (synovitis), or by autoimmune reactions, where the body launches an "attack" against its own substances and tissues. Other possible causes include:

- Reactions after an injury or surgery

- Pain from other conditions—such as arthritis, a rotator cuff tear, bursitis, or tendinitis—that has caused you to stop moving your shoulder

- Immobilization of your arm, such as in a sling, after surgery or fracture

Often, however, there is no known reason why adhesive capsulitis starts.

How Does it Feel?

Most people with adhesive capsulitis have worsening pain and then a loss of range of movement. Adhesive capsulitis can be broken down into 4 stages, and your physical therapist can help determine what stage you are in:

Stage 1 - "Pre-Freezing"

During this stage, it may be difficult to identify your problem as adhesive capsulitis. You've had symptoms for 1 to 3 months, and they're getting worse. There is pain with active movement and passive motion (movements that a physical therapist does for you). The shoulder usually aches when you're not using it, but pain increases and becomes "sharp" with movement. You'll have a mild reduction in motion during this period, and you'll protect the shoulder by using it less. The movement loss is most noticeable in "external rotation" (this is when you rotate your arm away from your body), but you might start to lose motion when you raise your arm (called "flexion and abduction")or reach behind your back (called "internal rotation"). You'll have pain during the day and at night.

Stage 2 – "Freezing"

By this stage, you've had symptoms for 3 to 9 months, most likely with a progressive loss of shoulder movement and an increase in pain (especially at night). The shoulder still has some range of movement, but this is limited by both pain and stiffness.

Stage 3 – "Frozen"

Your symptoms have persisted for 9 to 14 months, and you have greatly decreased range of shoulder movement. During the early part of this stage, there is still a substantial amount of pain. Toward the end of this stage, however, pain decreases, with the pain usually occurring only when you move your shoulder as far you can move it.

Stage 4 – "Thawing"

You've had symptoms for 12 to 15 months, and there is a big decrease in pain, especially at night. You still have a limited range of movement, but your ability to complete your daily activities involving overhead motion is improving at a rapid rate.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Often, physical therapists don't see patients with adhesive capsulitis until well into the freezing phase or early in the frozen phase. Your physical therapist will perform a thorough evaluation, including an extensive health history, to rule out other diagnoses. Your therapist will look for a specific pattern in your decreased range of motion; it's called a "capsular pattern" and is typical with adhesive capsulitis. In addition, your therapist will consider other conditions you might have—such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, and autoimmune disorders—that are associated with adhesive capsulitis.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Your physical therapist's overall goal is to restore your movement so that you can perform your activities and life roles. Once the evaluation process has identified the stage of your condition, your therapist will create an exercise program tailored to your needs. Exercise has been found to be most effective for those who are in stage 2 or higher.

Stages 1 and 2

Your physical therapist will help you maintain as much range of motion as possible and will help reduce the pain. Your therapist may use a combination of stretching and manual therapy techniques to increase your range of motion. The therapist also may decide to use treatments such as heat and ice to help relax the muscles prior to other forms of treatment. The therapist will give you a home exercise program designed to help reduce the loss of motion.

Stage 3

The focus of treatment will be on the return of motion, with your therapist using more aggressive stretching and manual therapy techniques. You may begin some strengthening exercises as well, and your home exercise program will change to include these exercises.

Stage 4

In the final stage, your therapist will focus on the return of "normal" shoulder body mechanics and your return to normal, everyday, pain-free activities. The therapist will continue to use stretching, strength training, and a variety of manual therapy techniques.

Sometimes, conservative care cannot reduce the pain. If this happens to you, your physical therapist may refer you for an injection of anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving medication into the joint space. Research has shown that although these injections don’t provide longer-term benefit for range of motion and don’t shorten the duration of the condition, they do offer short-term benefit in reducing pain.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

The cause of adhesive capsulitis is debatable, with no definitive cause, so there is no known method of prevention. The onset is usually gradual, with the disease process needing to "run its course."

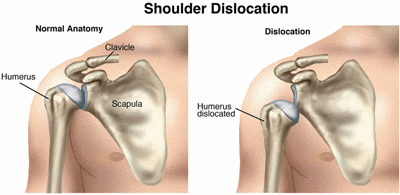

A joint dislocation is a separation of 2 bones where they meet at a joint. Joints may dislocate when a sudden impact causes the bones in the joint to shift out of place. Because the shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body and has such a wide range of motion, it is more likely to dislocate than any other joint in the body. Dislocations are among the most common traumatic injuries affecting the shoulder.

A shoulder dislocation most often occurs during contact sports, but everyday accidents such as falls can also cause the joint to dislocate. Athletes, non-athletes, children, and adults can all dislocate their shoulders.

A dislocated shoulder usually requires the assistance of a health care professional to guide the joint back into place. After the joint is realigned, physical therapists direct the rehabilitation of your shoulder as you recover, and can help you prevent reinjury.

A shoulder dislocation requires immediate medical attention, especially if you have:

- numbness in your arm or hand

- discoloration of arm or hand

- cold feelings in your arm

What is a Shoulder Dislocation?

The shoulder includes the clavicle (collar bone), scapula (shoulder blade), and humerus (upper-arm bone). The rounded top of the humerus and the cup-like end of the scapula fit together like a ball and socket. A shoulder dislocation can occur with an injury such as when you "fall the wrong way" on your shoulder or outstretched arm, forcing the shoulder beyond its normal range of movement and causing the humerus to come out of the socket. A dislocation can result in damage to many parts of the shoulder, including the bones, the ligaments, the labrum (the ring of cartilage that surrounds the socket), and the muscles and tendons around the shoulder joint.

How Does it Feel?

With most shoulder dislocations, you will feel the humerus coming out of the socket, followed by:

- Pain

- Inability to move the arm

- Awkward appearance of the shoulder

If you have any signs or symptoms of a nerve or blood vessel injury, seek immediate medical attention.

The humerus usually remains out of the socket until a physical therapist or other health care provider guides it back into place. X-rays are routinely taken after the dislocation is moved back into place to make sure you don’t have a fracture.

Occasionally, the shoulder may go back into place on its own. You might not even realize that you have dislocated your shoulder; you may only feel that you have injured it. If you have injured your shoulder and have pain, your physical therapist will review your health and injury history and conduct a physical examination.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

After the dislocated humerus has been moved back into position, your arm will be placed in a sling to protect you from reinjury and to make your shoulder more comfortable. Your physical therapist will show you how to apply ice to control pain and inflammation.

Your therapist will guide the rehabilitation of your shoulder and, based on the results of the examination and your goals, select treatments such as:

Range of-motion exercises. Swelling and pain can reduce your shoulder movement. Your physical therapist will teach you how to perform safe and effective exercises to restore full range of motion to your shoulder. In addition, the therapist might use a specialized technique called manual therapy to help you decrease pain in the shoulder.

Strengthening exercises. Based on how severe your injury is and where you are on the path to recovery, a physical therapist can determine which strengthening exercises are right for your shoulder. Poor strength of the shoulder muscles can result in the shoulder joint remaining unstable and possibly reinjuring.

Joint awareness and muscle re-training. Specialized exercises help your shoulder muscles re-learn how to respond to sudden forces. Your physical therapist will design these exercises to help you return to your normal activities.

Activity- or sport-specific training. Depending on the requirements of your job or the type of sports you play, you might need additional rehabilitation that is tailored for the demands your activities place on your shoulder. Your physical therapist can develop a program that takes all of these demands (as well as your specific injury) into account. For example, if you are an overhead thrower your physical therapist will guide you through a throwing progression and pay specific attention to your throwing mechanics.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

Unless they were traumatic injuries, shoulder dislocations can frequently be prevented. See your physical therapist if you:

- Have pain in your shoulder, especially when doing forceful activities

- Feel as though your shoulder is "slipping" or "moving"

- Hear a popping sound in your shoulder

If you already have a history of shoulder dislocation, you are at a greater risk for reinjury if your shoulder does not heal properly or if you do not regain your normal shoulder strength or joint awareness. Research shows that a very high percentage of dislocated shoulders will dislocate again. Physical therapists play an important role in helping people prevent recurring shoulder problems.

If you return to sports or activities too soon following injury, you could cause a reinjury. Your physical therapist can determine when you are ready to return to your activities and sports by making sure your shoulder is strong and ready for action. Your therapist will guide you through a rehabilitation program to restore your mobility, strength, joint awareness, and sport-specific skills. He or she may recommend a shoulder brace to allow you to gradually and safely return to your previous activities.

Treatment After Surgery

Following shoulder stabilization surgery, your arm will be placed in a sling, usually for 4 to 6 weeks. Right after surgery, your shoulder will be painful and stiff, and it might swell. You will be given pain medication to help control your pain; icing your shoulder will help reduce both the pain and the swelling.

Your physical therapist will guide you through your postsurgical rehabilitation, which will progress from gentle range-of-motion and strengthening exercises and ultimately to activity- or sport-specific exercises. The timeline for your recovery will vary depending on the surgical procedure and your general state of health, but full return to sports, heavy lifting, and other strenuous activities might not begin until 4 months after surgery. Your shoulder will be very susceptible to reinjury, so it is extremely important to follow the postoperative instructions provided by your surgeon and therapist.

Physical therapy after your shoulder surgery is essential to restore your shoulder’s function. Your rehabilitation typically will be divided into 4 phases:

- Phase I (maximal protection). This phase lasts for the first few weeks after your surgery, when your shoulder is at the greatest risk of reinjury. Your arm will be in a sling, and you likely will need assistance or some special strategies to accomplish everyday tasks such as bathing and dressing. Your physical therapist will teach you gentle range-of-motion and strengthening exercises, will provide hands-on techniques such as gentle massage, will offer advice on how you can reduce your pain, and might use cold compression or electrical stimulation to relieve pain.

- Phase II (moderate protection). This phase typically begins 1 month following surgery, with the goal of restoring mobility to the shoulder. You will reduce the use of your sling, and your range-of-motion and strengthening exercises will become more challenging. Your therapist will add exercises to strengthen the "core" muscles of your trunk and shoulder blade (scapula) and "rotator cuff" muscles—those are the muscles that provide additional support and stability to your shoulder. You will be able to begin using your arm for daily activities, but you'll still avoid any heavy lifting with your arm. Your therapist may use special joint mobilization techniques during this phase to help restore your shoulder's range of motion.

- Phase III (return to activity). This phase will typically begin about 3 months after surgery, with the goal of restoring your strength and joint awareness to equal that of your other shoulder. At this point, you should have full use of your arm for daily activities, but you will still be unable to participate in activities such as sports, yard work, or physically strenuous work-related tasks. Your physical therapist will increase the difficulty of your exercises by adding more weight or by having you use more challenging movement patterns. You might be able to start a modified weight-lifting or gym-based program during this phase.

- Phase IV (return to occupation/sport). This phase will typically begin 4 months after surgery with the goal of helping you return to sports, work, and other higher-level activities. Your physical therapist will instruct you in activity-specific exercises to meet your needs. For certain athletes, this may include throwing and catching drills. For others, it may include practice in lifting heavier items onto shelves or instruction in raking, shoveling, or housework. Your therapist also might recommend a shoulder brace to allow you to gradually and safely return to your activity level without reinjury.

Shoulder osteoarthritis (OA) is a condition that occurs when the cartilage that lines the sides of the shoulder joint is worn or torn away. It may be caused by injury or dislocation of the shoulder, or “wear and tear” of the shoulder over time. Shoulder OA develops most often in people in their 50s and beyond. As people misuse or overuse their joints over time, more cases are seen with each advancing decade of life. However, shoulder OA can also develop in younger people after trauma or surgery to a joint. The condition occurs more frequently in women than men. Physical therapists treat shoulder OA with hands-on therapy and individualized exercise programs.

Other Arthritis Resources:

- Community-Based Physical Activity Programs for Arthritis

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

What is Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder?

- Shoulder osteoarthritis (OA) occurs when the cartilage that lines the opposite sides of the shoulder joint becomes worn or torn. In the early stages of the condition, small pits develop in the smooth cartilage that lines each side of the joint. Eventually, small protrusions of bone, or "bone spurs" develop at the edges of the joint surfaces. Joint fluid may also accumulate under the cartilage, forming cysts, which can put pressure on the bone and may contribute to pain. In the late stages of the condition, the cartilage can wear away completely, allowing bone-to-bone contact.

- Two bones make up the shoulder joint. The bone at the top of the arm, the humerus, has a round, ball-shaped head, covered in cartilage. The bone on the body side of the joint is the scapula, or shoulder blade. The flat, cartilage-covered surface on the scapula that makes the other half of the shoulder joint is called the glenoid. The 2 sides of the shoulder joint are surrounded and connected by ligaments that control motion in the joint. The ligaments at the front of the shoulder become tightened as OA progresses. In addition, the four main muscles that surround the shoulder, known as the rotator cuff, may be over-used, weaken, or even tear. Rotator cuff conditions occur in about 90% of people with shoulder OA.

What causes osteoarthritis?

The exact cause isn't known. Osteoarthritis may be hereditary, which means it runs in families. Osteoarthritis seems to be related to the wear and tear put on joints over the years in most people. But wear and tear alone don't cause osteoarthritis.

How Does it Feel?

Shoulder OA may cause you to experience:

- Pain with activities that relieves with rest

- Decreased shoulder movement (range of motion), especially when reaching back as if grabbing a seat belt

- Weakness

- Stiffness and eventual difficulty using the affected arm

- Pain at rest and difficulty sleeping as the condition worsens

How Is It Diagnosed?

- Your doctor may order an x-ray to determine the amount of change in the joint. As the cartilage wears down, it decreases the space between the bones visible on these images. Bone spurs or cysts may also be present. Apparent damage often does not directly correlate with your pain. If there is suspected loss of bone, a CAT scan (computerized topography) may be ordered to get a clearer picture of the area.

- Your physical therapist will ask questions about how the shoulder problem is affecting your life, and what activities are now difficult for you. Describing your pain will help determine the best plan for your treatment. Your physical therapist will evaluate how far the shoulder can move, both as you move your arm and as he or she moves it for you. The examination will include evaluating the strength of the muscles of the rotator cuff and those that support the shoulder blade. The physical therapist may look at your posture and how you perform certain activities and movements to see how they affect your shoulder.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Without Surgery

When someone develops shoulder pain, the first recommended treatment is physical therapy. The following treatments can help decrease pain, improve movement, and allow increased use of your shoulder for daily activities. They may prolong the time until surgery is needed, or help you avoid it altogether.

- Improving tolerance of daily activities. Your physical therapist will work with you to help you get back to performing your daily tasks. Just changing your posture can reduce the pressure and forces at the joint and help reduce your pain. He or she may recommend the use of physical therapy "modalities" such as heat and cold, teach you about proper movement, and help you modify your activities to control your pain.

- Improving shoulder mobility. Your physical therapist can recommend ways to restore shoulder movement (range of motion). Stretching can lengthen tight muscles and ligaments, improving your posture and movement. Shoulder-joint mobilization may help improve movement and ease your pain. Your physical therapist may gently move your shoulder (manual therapy), to stretch the ligaments in ways normal stretching or arm motions do not.

- Improving the strength of your muscles. Strengthening the rotator cuff muscles can reduce the friction caused by the rough arthritic surfaces of the shoulder joint rubbing together. Support from the muscles that maintain your posture can help reduce forces on the shoulder joint.

Other options for treatment may include medications such as steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Injections of steroid or anesthetic medications may also help.

Following Surgery

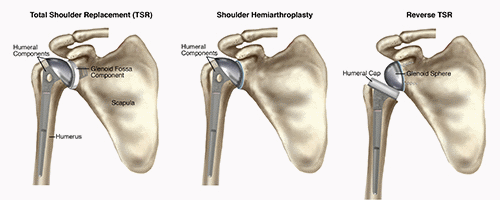

There are several surgical options for treating shoulder OA, depending on the degree of damage at the joint and its surrounding structures, and your age, activity level, and occupation.

Palliative Options: The goal of this surgery is to resolve symptoms; it does not restore or reconstruct the arthritic area. This option is best for people under the age of 65 with minimal cartilage problems, or people in their 20s to 40s with many active years ahead.

Reparative, Restorative, and Reconstructive Options: Over the last several years, surgeons have developed new "biologic resurfacing" techniques for younger people who have shoulder OA who are not yet ready for total shoulder replacement. Your doctor and physical therapist can describe them in detail for you.

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty (TSA): Total shoulder arthroplasty is the medical term for a shoulder replacement. This is the best surgical technique for older patients with advanced OA who have good quality of bone at the shoulder joint and intact rotator cuff muscles. This procedure is best for people who do not plan to do high-level activities (overhead work at a job, overhead sports, or significant amounts of heavy lifting).

Shoulder Hemiarthroplasty: Shoulder hemiarthroplasty is a partial replacement of the joint. It is an option if the muscles that make up the rotator cuff of the shoulder are too weak or damaged to properly support and move the joint.

Reverse (Inverse) Total Shoulder Arthroplasty (rTSA): This surgery is also an option when the muscles that make up the rotator cuff of the shoulder have failed or are irreparable, or a complex fracture is present.

Arthroscopy: Many shoulder surgeries can be done via arthroscopy, a less invasive surgery by which the surgeon makes small incisions in the skin and inserts pencil-sized instruments (with a camera) into the joint to repair damage.

Postsurgical physical therapy varies based on the procedure performed. It may include:

- Ensuring your safety as you heal. Your surgeon and physical therapist work together as a team to return your shoulder to health. After the surgeon completes his or her work, your work begins. You will perform specific activities and exercises at the correct time to allow for optimal healing. All surgical procedures modify your shoulder joint and surrounding tissues. Restorative and reconstructive options may take several months to heal, with longer precautions.

- Aiding motion of the shoulder. After surgery, your shoulder will be sore and swollen, and you may not feel like moving your arm. However, gentle motion is often recommended. Your physical therapist may move your arm or assist you in moving your arm to begin to gently restore movement. After some surgeries, movement is restricted during healing; your physical therapist and surgeon will choose the best options for recovery and guide you through the process.

- Strengthening the shoulder. Due to prior disuse or postoperative pain, your muscles may not be as strong as normal. If the muscle was repaired during surgery, you will have to let it heal for a period of time, and your physical therapist can let you know what activity is safe to help the healing along.

- Relieving your pain. Using manual (hands-on) therapies and other modalities, your physical therapist can help reduce your pain during exercise and daily activities.

- Getting back to work and activities of daily living. Returning to work and daily activities may be slow, and your physical therapist will guide you through the process to achieve the best results.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

There is no way to prevent shoulder OA. You may reduce your risk by staying moderately active, keeping the shoulder strong, and keeping the shoulder muscles the appropriate length with stretching. Your physical therapist can help you determine what exercises will keep your shoulder healthy. Eating healthy and exercising will help you manage a healthy weight and healthy joints. Avoiding injuries to the shoulder joint will help reduce your risk of OA as well.

Shoulder Arthoplasty (Total Shoulder Replacement)

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), often called a total shoulder replacement, is a surgical procedure in which part or all of the shoulder joint is replaced. It is estimated that 53,000 people in the United States have shoulder replacement surgery each year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. That number compares to the more than 900,000 Americans a year who have knee and hip replacement surgery. Physical therapists can help patients who undergo a TSA return to their previous levels of physical activity, including fitness training, or participation in sports like swimming or golf.

What is Total Shoulder Arthoplasty?

Total shoulder arthroplasty is a surgical procedure in which part or all of the shoulder joint is replaced. It is performed on the shoulder when medical interventions, such as other conservative surgeries, medication, and physical therapy no longer provide pain relief. The decision to have a TSA is made following consultation with your orthopedic surgeon and your physical therapist.

shoulder replacement may be needed if you have any of the following conditions affecting the shoulder, causing severe shoulder pain and limiting your ability to use the affected shoulder:

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Severe shoulder fracture

- Rotator cuff disease (a muscle tear or soft-tissue breakdown of the rotator cuff)

- Osteonecrosis of the shoulder (death of the bone tissue at the head of the humerus)

A TSA involves removing the ends of the bone at the shoulder joint, and replacing them with artificial parts. The upper part of the arm bone (humerus) is shaped like a ball; it is called the "head" of the humerus. During a TSA, the head of the humerus is replaced by a metal ball. The socket that the head of the humerus sits in is called the glenoid fossa. During a TSA, the socket is replaced by a plastic cup.

Due to various physical limitations, your orthopedic surgeon may decide that you are a candidate for another form of TSA, such as:

- Shoulder hemiarthroplasty, where only the head of the humerus is replaced with a metal ball.

- Reverse TSA, where the metal ball and plastic socket are reversed. This procedure is recommended when the rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder are damaged. The plastic socket is attached to the top of the humerus, and the metal ball is attached to the socket. This procedure allows another shoulder muscle, called the deltoid, to take over for the damaged rotator cuff muscles, improving functional range of motion, strength, and stability of the shoulder

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Physical therapy plays a vital role in ensuring a safe recovery by improving shoulder function, and limiting pain following a TSA. Your physical therapist will work with you prior to and following your surgery, to help you safely return to your previous levels of activity, including performing household chores, job duties, and recreational activities.

Before Surgery

The better physical condition your shoulder is in prior to surgery, the better your recovery will be. Your physical therapist will teach you exercises to build shoulder strength, and improve your shoulder and upper back movement to keep the shoulder as strong and mobile as possible up until the time of surgery.

After Surgery

Your physical therapist will educate you about precautions to take after surgery, such as wearing a sling to perform all activities, and gradually beginning to safely move your arm. If you are a smoker, quitting smoking will improve your healing process.

After your TSA, you will likely stay in the hospital for 2 to 3 days. If you have other medical conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, your hospital stay may be a few days longer. Your shoulder will be placed in a sling for the next 2 to 6 weeks; you will be advised to not move your shoulder on your own.

Your physical therapy will begin within a day or two of your surgery. A hospital physical therapist will visit your room to teach you how to perform simple tasks like brushing your teeth, and tell you what movements (such as pushing, pulling, or reaching with the affected arm) you simply cannot perform. Your physical therapist will teach you how to get in and out of bed safely, how to get the sling on and off, and how to get dressed while keeping your shoulder in a safe position. You will also learn how to minimize pain and swelling in the area by applying an ice pack, and elevating the upper arm.

You may need some help from friends or family members with daily activities for the first few days or weeks after your surgery. You will not be able to drive for the first few weeks after surgery.

As You Recover

When you are discharged from the hospital, continuation of physical therapy is essential. Your surgeon and physical therapist will work as a team to ensure your safe recovery. Your physical therapist will teach you exercises that may include:

Range-of-Motion Exercises. It is important to not move your shoulder suddenly or with any force for the first 2 to 6 weeks following surgery, to allow proper healing. Your physical therapist will passively move your shoulder in different directions to allow you to safely begin regaining movement. Your physical therapist will also teach you gentle exercises to perform at home. You will also learn range-of-motion exercises for the elbow and hand, so these joints do not get stiff from being held in a sling. Squeezing a ball or putty will help keep your grip strong, while your shoulder recovers. You will use ice packs on the shoulder and elevate your arm on pillows to allow gravity to help reduce the swelling in the shoulder, as instructed by your physical therapist.

Strengthening Exercises. As your shoulder mobility returns within a few weeks or months, your physical therapist will guide you through a shoulder strengthening program. You may use resistive bands and weights to perform gentle strengthening exercises.

Functional Training. Your physical therapist will help you regain everyday shoulder movements, such as reaching into a cupboard, reaching behind your body to tuck in your shirt, or reaching across your body to fasten a seat belt.

Job and Sport-Specific Training. Your physical therapist will design a personalized program to enable you to resume your job tasks without pain. These may include reaching, pushing, or carrying movements. You will also receive sport-specific training if you are planning to return to a sport. Your physical therapist will create a specialized home or fitness-center exercise program based on your individual needs, to be continued long after formal physical therapy has been completed.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

If you begin noticing your shoulder is painful and you are losing the ability to move your shoulder, a physical therapist can help. A properly designed exercise program can delay or even help you avoid surgery. A physical therapist will teach you specific, safe exercises to improve your shoulder flexibility and strength, and teach you how to manage your pain. Proper nutrition and physical activity will keep all of your joints healthy. Avoiding smoking is essential for proper healing and overall recovery from any injury.

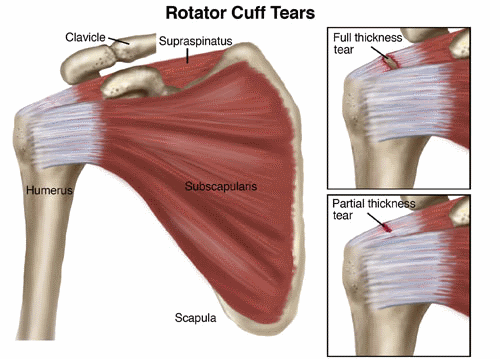

The "rotator cuff" is a group of 4 muscles that are responsible for keeping the shoulder joint stable. Unfortunately, injuries to the rotator cuff are very common, either from injury or with repeated overuse of the shoulder. Injuries to the rotator cuff can vary as a person ages. Rotator cuff tears are more common later in life, but they also can occur in younger people. Athletes and heavy laborers are commonly affected; older adults also can injure the rotator cuff when they fall or strain the shoulder, such as when walking a dog that pulls on the leash. When left untreated, this injury can cause severe pain and a decrease in the ability to use the arm.

What is a Rotator Cuff Tear?

The "rotator cuff" is a group of 4 muscles and their tendons (which attach them to the bone). These muscles connect the upper-arm bone, or humerus, to the shoulder blade. The important job of the rotator cuff is to keep the shoulder joint stable. Sometimes, the rotator cuff becomes inflamed or irritated due to heavy lifting, repetitive arm movements, or a fall. A rotator cuff tear occurs when injuries to the muscles or tendons cause tissue damage or disruption.

Rotator cuff tears are called either "full-thickness" or partial-thickness," depending on how severe they are. Full-thicknesstears extend from the top to the bottom of a rotator cuff muscle/tendon. Partial-thickness tears affect at least some portion of a rotator cuff muscle/tendon, but do not extend all the way through.

Tears often develop as a result of either a traumatic event or long-term overuse of the shoulder. These conditions are commonly called acute or chronic:

- An acute rotator cuff tear is one that just recently occurred, often due to a trauma such as a fall or lifting a heavy object.

- Chronic rotator cuff tears are much slower to develop. These tears are often the result of repeated actions with the arms working above shoulder level—such as with ball-throwing sports or certain work activities.

People with chronic rotator cuff injuries often have a history of rotator cuff tendon irritation that causes shoulder pain with movement. This condition is known as shoulder impingement syndrome (SIS).

Rotator cuff tears also may occur in combination with injuries or irritation of the biceps tendon at the shoulder, or with labral tears (to the ring of cartilage at the shoulder joint).

How Does it Feel?

Rotator cuff tears can cause:

- Pain over the top of the shoulder or down the outside of the arm

- Shoulder weakness

- Loss of shoulder motion

The injured arm often feels heavy, weak, and painful. In severe cases, tears may keep you from doing your daily activities or even raising your arm. People with rotator cuff tears often are unable to lift the arm to reach high shelves or reach behind their backs to tuck in a shirt or blouse, pull out a wallet, or fasten a bra.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Your physical therapist will review your health history, perform a thorough examination, and conduct a series of tests designed specifically to help pinpoint the cause of your shoulder pain.

Physical therapists perform specialized tests--such as the Hawkins-Kennedy impingement test, Neer's impingement sign, and the external rotation lag sign-- to diagnose an impingement or a tear. For instance, your therapist may raise your arm, move your arm out to the side, or raise your arm and ask you to resist a force, all at specific angles of elevation. These tests may cause you to feel some temporary discomfort, but don't worry—that's normal and part of what helps the therapist identify the exact source of your problem.

In some cases, the results of these tests might indicate the need for a referral to an orthopedist or for imaging tests, such as ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT).

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Once a rotator cuff injury has been diagnosed, you will work with your orthopedist and physical therapist to decide if you should have surgery or if you can try to manage your recovery without surgery. If you don't have surgery, your therapist will work with you to restore your range of motion, muscle strength, and coordination, so that you can return to your regular activities. In some cases, your therapist may help you learn to modify your physical activity so that you put less stress on your shoulder. If you decide to have surgery, your therapist can help you both before and after the procedure.

Regardless of which treatment you have—physical therapy only, or surgery and physical therapy—early treatment can help speed up healing and avoid permanent damage.

If You Have an Acute Injury

If a rotator cuff tear is suspected following a trauma, seek the attention of a physical therapist or other health care provider to rule out the possibility of serious life- or limb-threatening conditions. Once serious injury is ruled out, your physical therapist will help you manage your pain and will prepare you for the best course of treatment.

If You Have a Chronic Injury

A physical therapist can help manage the symptoms of chronic rotator cuff tears as well as improve how your shoulder works. For large rotator cuff tears that can't be fully repaired, physical therapists can teach special strategies to improve shoulder movement.

If You Have Surgery

Once a full-thickness rotator cuff tear develops, you may need surgery to restore use of the shoulder or decrease painful symptoms. Physical therapy is an important part of the recovery process. The repaired rotator cuff is vulnerable to reinjury following shoulder surgery, so it's important to work with a physical therapist to safely regain full use of the injured arm. After the surgical repair, you will need to wear a sling to keep your shoulder and arm protected as the repair heals. Once you are able to remove the sling for exercise, the physical therapist will begin your exercise program.

Your physical therapist will design a treatment program based on both the findings of the evaluation and your personal goals. He or she will guide you through your postsurgical rehabilitation, which will progress from gentle range-of-motion and strengthening exercises and ultimately to activity- or sport-specific exercises. Your treatment program most likely will include a combination of exercises to strengthen the rotator cuff and other muscles that support the shoulder joint. Your therapist will instruct you in how to use therapeutic resistance bands. The timeline for your recovery will vary depending on the surgical procedure and your general state of health, but full return to sports, heavy lifting, and other strenuous activities might not begin until 4 months after surgery. Your shoulder will be very susceptible to reinjury, so it is extremely important to follow the postoperative instructions provided by your surgeon and physical therapist.

Physical therapy after your shoulder surgery is essential to restore your shoulder's function. Your rehabilitation will typically be divided into 4 phases:

- Phase I (maximal protection). This phase lasts for the first few weeks after your surgery, when your shoulder is at the greatest risk of reinjury. During this phase, your arm will be in a sling. You will likely need assistance or need strategies to accomplish everyday tasks such as bathing and dressing. Your physical therapist will teach you gentle range-of-motion and isometric strengthening exercises, will provide hands-on techniques such as gentle massage, will offer advice on reducing your pain, and may use cold compression and electrical stimulation to relieve pain.

- Phase II (moderate protection). This next phase has the goal of restoring mobility to the shoulder. You will reduce the use of your sling, and your range-of-motion and strengthening exercises will become more challenging. Exercises will be added to strengthen the "core" muscles of your trunk and shoulder blade (scapula) and "rotator cuff" muscles that provide additional support and stability to your shoulder. You will be able to begin using your arm for daily activities, but will still avoid any heavy lifting with your arm. Your physical therapist may use special hands-on mobilization techniques during this phase to help restore your shoulder's range of motion.

- Phase III (return to activity). This phase has the goal of restoring your strength and joint awareness to equal that of your other shoulder. At this point, you should have full use of your arm for daily activities, but you will still be unable to participate in activities such as sports, yard work, or physically strenuous work-related tasks. Your physical therapist will advance the difficulty of your exercises by adding more weight or by having you use more challenging movement patterns. A modified weight-lifting/gym-based program may also be started during this phase.

- Phase IV (return to occupation/sport). This phase will help you return to sports, work, and other higher-level activities. During this phase, your physical therapist will instruct you in activity-specific exercises to meet your needs. For certain athletes, this may include throwing and catching drills. For others, it may include practice in lifting heavier items onto shelves, or instruction in raking, shoveling, or housework.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

A physical therapist can help you decrease your risk of developing or worsening a rotator cuff tear, especially if you seek assistance at the first sign of shoulder pain or discomfort. To avoid developing or progressing to a rotator cuff tear from an existing shoulder impingement, it is imperative to avoid future exacerbations. Your physical therapist can help you strengthen your rotator cuff muscles, train you to avoid potentially harmful positions, and determine when it is appropriate for you to return to your normal activities.

General Tips:

- Avoid repeated overhead arm positions that may cause shoulder pain. If your job requires such movements, seek out the advice of a physical therapist to learn arm positions that may be used with less risk.

- Apply rotator cuff muscle and scapular strengthening exercises into your normal exercise routine. The strength of the rotator cuff is just as important as the strength of any other muscle group. To avoid potential detriment to the rotator cuff, general strengthening and fitness programs may improve shoulder health.

- Practice good posture. A forward position of the head and shoulders has been shown to alter shoulder blade position and create shoulder impingement syndrome.

- Avoid sleeping on your side with your arm stretched overhead, or lying on your shoulder. These positions can begin the process that causes rotator cuff damage.

- Avoid carrying heavy objects at your side; this can strain the rotator cuff.

- Avoid smoking; it can decrease the blood flow to your rotator cuff.

- Consult a physical therapist at the first sign of symptoms.

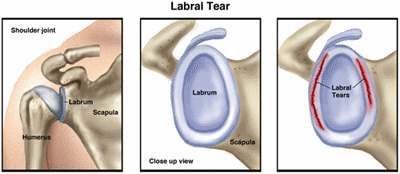

What is a Shoulder Labral Tear?

The glenoid labrum provides extra support for the shoulder joint, helping to keep it in place. A labral tear occurs when part of this ring is disrupted, frayed, or torn. Tears may lead to shoulder pain, an unstable shoulder joint, and, in severe cases, dislocation of the shoulder. Likewise, a shoulder dislocation can result in labral tears.

When you think of the shoulder joint, picture a golf ball (the head of the upper-arm bone, or humerus) resting on a golf tee (the glenoid fossa, a shallow cavity or socket located on the shoulder blade, or scapula). The labrum provides a rim for the socket (golf tee) so that the humerus (golf ball) does not easily fall off. If the labrum is torn, it is harder for the humerus to stay in the socket. The end result is that the shoulder joint becomes unstable and prone to injury.

Because the biceps tendon attaches to the shoulder blade through the labrum, labral tears can occur when you put extra strain on the biceps muscle, such as when you throw a ball. Tears also can result from pinching or compressing the shoulder joint when the arm is raised overhead. There are 2 types of tears:

- Traumatic labral tears usually happen because of a single incident, such as a shoulder dislocation or an injury from heavy lifting. People who use their arms raised over their heads—such as weight lifters, gymnasts, and construction workers—are more likely to have traumatic labral tears. Activities the force is at a distance from the shoulder, such as striking a hammer or swinging a racquet, also can create shoulder joint problems.

- Nontraumatic labral tears most often occur because of muscle weakness or shoulder joint instability. When the muscles that stabilize the shoulder joint are weak, more stress is put on the labrum, leading to a tear. People with nontraumatic tears tend to have more "looseness" or greater mobility throughout all their joints, which might be a factor in the development of a tear.

How Does it feel?

With a shoulder labral tear, you might have:

- Pain over the top of your shoulder

- "Popping," "clunking," or "catching" with shoulder movement, because the torn labrum has "loose ends" that are flipped or rolled within the shoulder joint during arm movement and that may even become trapped between the upper arm and shoulder blade

- Shoulder weakness, often on one side

- A feeling that your shoulder joint will pop out

How Is It Diagnosed?

Not all shoulder labral tears cause symptoms. In fact, when tears are small, many people are able to function without pain. In some instances, the labrum might even heal on its own, if care is taken not to stress the injured tissues. Due to the lack of blood supply available at the labrum, complete healing may be difficult. The shoulder with a labral tear may pop or click without being painful; however, if a tear progresses, it is likely to lead to pain and weakness.

If your physical therapist suspects that you may have a labral tear, the therapist will review your health history and perform an examination that is designed to test the condition of the glenoid labrum (the ring of cartilage at the base of the shoulder). The tests will place your shoulder in positions that may recreate some of your symptoms, such as "popping," "clicking," or mild pain. Using this examination, your physical therapist will determine whether your shoulder joint is unstable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also may be used. Labral tears may be difficult to diagnose with certainty without arthroscopic surgery, where a tube-like instrument called an arthroscope is inserted into the joint through a small incision to view or repair an injury.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

When shoulder labral tears cause minor symptoms but don’t cause shoulder instability, they usually are treated with physical therapy. Your physical therapist will:

- Educate you about positions or activities to avoid

- Tailor a treatment plan for your recovery

- Design specific shoulder strengthening exercises, such as external rotation and internal rotation exercises, to help support the joint and decrease strain on the glenoid labrum

- Design stretching exercises, such as the cross-body stretch or the doorway stretch, to help improve the function of the muscles surrounding the shoulder

- Perform a special technique called manual therapy to decrease pain and improve movement

In more severe cases, when conservative treatments are unable to completely relieve the symptoms of a labral tear, surgery may be required to re-attach the torn labrum. Following surgery, your physical therapist will show you how to slowly and safely return to your daily activities.

A surgically repaired labrum takes 9 to 12 months to completely heal. Immediately following the repair, you should avoid putting excessive stress or strain on the repaired labrum and should increase stress to your shoulder slowly over time. Your physical therapist is trained to gradually introduce activity in a safe manner to allow you to return to your usual activities without re-injuring the repaired tissues.

Can this Injury or Condition be prevented?

Forceful activities with the arms raised overhead may increase the likelihood of developing a labral tear. To avoid putting excessive stress on the labrum, you need to develop strength in the muscles that surround the shoulder and scapula. Your therapist will:

- Design exercises to help you strengthen your shoulder

- Show you how to avoid potentially harmful positions

- Determine when it is appropriate for you to return to your normal activities

- Train you to properly control your shoulder movement and modify your activities to reduce your risk of sustaining a labral injury

Shoulder bursitis is a painful condition that affects people of all ages. The condition tends to develop more in middle-aged, elderly, and individuals who have muscle weakness. Shoulder bursitis can have many causes, but the most common is a repetitive activity, such as overhead reaching, throwing, or arm-twisting, which creates friction in the upper shoulder area. Athletes often develop shoulder bursitis after throwing, pitching, or swimming repetitively. The condition can happen gradually or suddenly, or can be a result of an autoimmune disease. It can also occur without any specific cause. Physical therapy can be a very effective treatment for shoulder bursitis to reduce pain, swelling, stiffness, and associated weakness in the shoulder, arm, neck, and upper back.

Shoulder impingement and tendinitis can occur along with shoulder bursitis. A physical therapist can effectively treat all of these conditions together.

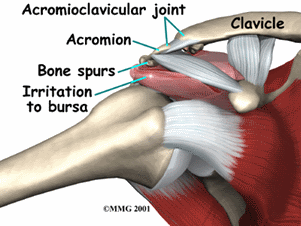

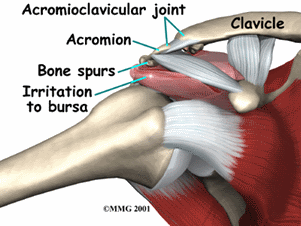

What is Shoulder Bursitis?

Shoulder bursitis (also called subacromial bursitis) occurs when the bursa (a fluid-filled sac on the side of the shoulder) becomes damaged, irritated, or inflamed. Bursitis ("-itis"); means "inflammation") means the bursa has become irritated and inflamed, which causes pain. Normally, the bursa acts as a cushion for the rotator cuff tendon of the supraspinatus muscle that sits under the bursa, and prevents the tendon from rubbing on the acromion bone above the bursa. Certain positions, motions, or disease processes can cause friction or stress on the bursa, leading to the development of bursitis. When the bursa becomes injured, the tendon doesn't glide smoothly over it, and can become painful.

Shoulder bursitis can be caused by:

- Repetitive motions (overhead reaching or lifting, throwing, or twisting of the arm)

- Muscle weakness or poor muscle coordination

- Incorrect posture

- Direct trauma (being hit, or falling on, the side of the shoulder)

- Shoulder surgery or replacement

- Calcium deposits in the shoulder

- Overgrowth or bone spurs in the acromion bone

- Infection

- Autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, psoriasis, or thyroid disease

- Muscles or tendons in the shoulder area rubbing the bursa and causing irritation

How Does it Feel?

With shoulder bursitis, you may experience:

- Pain on the outer side or tip of the shoulder

- Pain when you push with your finger on the tip of the shoulder

- Pain when lying on the affected shoulder

- Pain that worsens when lifting the arm to the side

- Pain when rotating the arm

- Pain when pushing or pulling open a door

How Is It Diagnosed?

If you see your physical therapist first, the physical therapist will conduct a thorough evaluation that includes taking your health history. Your physical therapist also will ask you detailed questions about your injury, such as:

- How and when did you notice the pain?

- Have you been performing any repetitive activity?

- Did you receive a direct hit to the shoulder, or fall on it?

Your physical therapist also will perform special tests to help determine the likelihood that you have shoulder bursitis. Your physical therapist will gently press on the outer side of the shoulder to see if it is painful to the touch, and may use additional tests to determine if other parts of your shoulder are injured. The physical therapist also will observe your posture, and how you lift your arm.

Your physical therapist will test and screen for other, more serious conditions that could cause shoulder pain. To provide a definitive diagnosis, your physical therapist may collaborate with an orthopedic physician or other health care provider, who may order further tests, such as an X-ray to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other damage to the shoulder, such as a fracture.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Your physical therapist will work with you to design a specific treatment program that will speed your recovery, including exercises and treatments that you can do at home. Physical therapy will help you return to your normal lifestyle and activities. The time it takes to heal the condition varies, but results can often be achieved in 2 to 8 weeks, when a proper stretching and strengthening program is implemented.

During the first 24 to 48 hours following your diagnosis, your physical therapist may advise you to:

- Rest the area by avoiding lifting or reaching overhead, or any activity that causes pain.

- Apply ice packs to the area for 15 to 20 minutes every 2 hours.

- Consult with a physician for further services, such as medication or diagnostic tests.

Your physical therapist will work with you to:

Reduce Pain and Swelling. If repetitive activities have caused the shoulder bursitis, your physical therapist will help you understand how to avoid or modify the activities to allow healing to begin. Your physical therapist may use different types of treatments and technologies to control and reduce your pain and swelling, including ice, heat, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, taping, specific exercises, and hands-on therapy, such as specialized massage.

Improve Motion. Your physical therapist will choose specific activities and treatments to help restore normal movement in the shoulder and arm. These might begin with "passive" motions that the physical therapist performs for you to gently move your shoulder joint, and progress to active exercises and stretches that you do yourself.

Improve Flexibility. Your physical therapist will determine if any shoulder, arm, chest, or neck muscles are tight, start helping you to stretch them, and teaching you how to stretch them.

Improve posture. If posture problems are found to be related to your condition, your physical therapist will work with you to help improve your posture to help alleviate your pain, and prevent future recurrence.

Improve Strength. Shoulder bursitis is often related to weak, injured, or uncoordinated shoulder muscles. Certain exercises will aid healing at each stage of recovery; your physical therapist will choose and teach you the correct exercises and equipment to use to steadily restore your strength and agility. These may include using cuff weights, stretch bands, and weight lifting equipment.

Improve Endurance. Regaining your muscular endurance in the shoulder is important after an injury. Your physical therapist will teach you exercises to improve your muscular endurance, so you can return to your normal activities. Cardio-exercise equipment may be used, such as upper-body ergometers, treadmills, or stationary bicycles.

Learn a Home Program. Your physical therapist will teach you strengthening and stretching exercises to perform at home. These exercises will be specific for your needs; if you do them as prescribed by your physical therapist, you can speed your recovery.

Return to Activities. Your physical therapist will discuss your activity goals with you and use them to set your work, sport, and home-life recovery goals. Your treatment program will help you reach your goals in the safest, fastest, and most effective way possible. Your physical therapist will teach you exercises, work retraining activities, and sport-specific techniques and drills to help you achieve your goals.

Speed Recovery Time. Your physical therapist is trained and experienced in choosing the best treatments and exercises to help you safely heal, return to your normal lifestyle, and reach your goals faster than you are likely to do on your own.

If Surgery Is Necessary

Surgery is not commonly required for shoulder bursitis. But if surgery is needed, you will follow a recovery program over several weeks, guided by your physical therapist. Your physical therapist will help you minimize pain, regain motion and strength, and return to normal activities in the safest and speediest manner possible.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

Your physical therapist can recommend a home-exercise program to strengthen and stretch the muscles around your shoulder, arm, chest, and neck to help prevent future injury. These may include strength and flexibility exercises for the shoulder, arm, chest, neck, and core muscles.

To help prevent a recurrence of the injury, your physical therapist may advise you to:

- Follow a consistent flexibility and strengthening exercise program, especially for the shoulder muscles, to maintain good physical conditioning, even in a sport's off-season or after you retire from sports.

- Always warm up before starting a sport or heavy physical activity.

- Learn and maintain good posture.

- Gradually increase any demanding activity, rather than suddenly increasing the activity amount or intensity. This includes household activities, office work, or athletics.

- Learn and maintain correct posture.

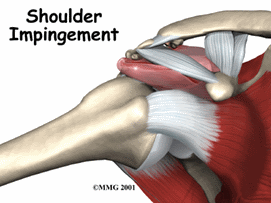

Shoulder impingement syndrome occurs as the result of chronic and repetitive compression or "impingement" of the rotator-cuff tendons in the shoulder, causing pain and movement problems. It can also be caused by an injury to the shoulder. People who perform repetitive or overhead arm movements, such as manual laborers or athletes who raise their arms repeatedly overhead (ie, weightlifters and baseball pitchers), are most at risk for developing a shoulder impingement. Poor posture can also contribute to its development. If left untreated, a shoulder impingement can lead to more serious conditions, such as a rotator cuff tear. Physical therapists can help decrease pain, and improve shoulder motion and strength in people with shoulder impingements.

What is Shoulder Impingement?

Shoulder impingement syndrome is a condition that develops when the rotator-cuff tendons in the shoulder are overused or injured, causing pain and movement impairments. Shoulder impingement syndrome may also be referred to as "subacromial" impingement syndrome because the tendons, ligaments, and bursa under the "acromion" can become pinched or compressed. The shoulder is made up of 3 bones called the humerus, the scapula, and the clavicle. The acromion is a bony prominence on the top of the scapula, which can be felt as a bump at the tip of the shoulder.

The rotator cuff tendon and the bursa sit beneath the acromion. The bursa is a fluid-filled sac that provides a cushion between the bony acromion and the rotator cuff tendon, and it can become compressed underneath the acromion.

Impingement symptoms can occur when compression and microtrauma harm the tendons. There are several causes to shoulder impingement syndrome including:

- Repetitive overhead movements, such as golfing, throwing, racquet sports, and swimming, or frequent overhead reaching or lifting.

- Injury, such as a fall, where the shoulder gets compressed.

- Bony abnormalities of the acromion, which narrow the subacromial space.

- Osteoarthritis in the shoulder region.

- Poor rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscle strength, causing the humeral head to move abnormally.

- Thickening of the bursa.

- Thickening of the ligaments in the area.

- Tightness of the soft tissue around the shoulder joint called the joint capsule.

How Does it Feel?

Individuals with shoulder impingement may experience:

- Restriction in shoulder motion with associated weakness in movement patterns, such as reaching overhead, behind the body, or out to the side.

- Pain in the shoulder when moving the arm overhead, out to the side, and beside the body.

- Pain and discomfort when attempting to sleep on the involved side.

- Pain with throwing motions and other dynamic movement patterns.

How Is It Diagnosed?

A physical therapist will perform an evaluation and ask you questions about the pain you are feeling, and other symptoms. Your physical therapist may perform strength and motion tests on your shoulder, ask about your job duties and hobbies, evaluate your posture, and check for any muscle imbalances and weakness that can occur between the shoulder and the scapular muscles.

Special tests involving gentle movements of your arm and shoulder may be performed to determine exactly which tendons are involved. X-rays may also be taken to identify other conditions that could be contributing to your discomfort, such as bony spurs or abnormalities, or arthritis.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

It is important to get proper treatment for shoulder impingement as soon as it occurs. Secondary conditions can result from the impingement of the tissues in the shoulder, including irritation of the bursa and rotator-cuff tendinitis or tears.

Physical therapy can be very successful in treating shoulder impingement syndrome. You will work with your physical therapist to devise a treatment plan that is specific to your condition and goals. Your individual treatment program may include:

Pain Management. Your physical therapist will help you identify and avoid painful movements, as well as correct abnormal postures to reduce impingement compression. Therapeutic modalities, like iontophoresis (medication delivered through an electrically charged patch) and ultrasound may be applied. Ice may also be helpful to reduce pain.

Manual Therapy. Your physical therapist may use manual techniques, such as gentle joint movements, soft-tissue massage, and shoulder stretches to get your shoulder moving properly, so that the tendons and bursa avoid impingement.

Range-of-Motion Exercises. You will learn exercises and stretches to help your shoulder and shoulder blade move properly, so you can return to reaching and lifting without pain.

Strengthening Exercises. Your physical therapist will determine which strengthening exercises are right for you, depending on your specific condition. Often with shoulder impingement syndrome, the head of the humerus tends to drift forward and upward due to the rotator-cuff muscles becoming weak. Strengthening the rotator-cuff and scapular muscles helps position the head of the humerus bone down and back to ease the impingement. You may also perform resistance training exercises to strengthen your weaker muscles. You will receive a home-exercise program to continue your strengthening long after you have completed your formal physical therapy.

Patient Education. Learning proper posture is an important part of rehabilitation. For example, when your shoulders roll forward as you lean over a computer, the tendons in the front of the shoulder can become impinged. Your physical therapist will work with you to help improve your posture, and may suggest adjustments to your work station and work habits.

Functional Training. As your symptoms improve, your physical therapist will teach you how to correctly perform a range of functions using proper shoulder mechanics, such as lifting an object onto a shelf or throwing a ball. This training will help you return to pain-free function on the job, at home, and when playing sports.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

Shoulder impingement syndrome can be prevented by:

- Maintaining proper strength in the shoulder and shoulder-blade muscles.

- Regularly stretching the shoulders, neck, and middle-back region.

- Maintaining proper posture and shoulder alignment when performing reaching and throwing motions.

- Avoiding forward-head and rounded-shoulder postures (being hunched over) when spending long periods of time sitting at a desk or computer.

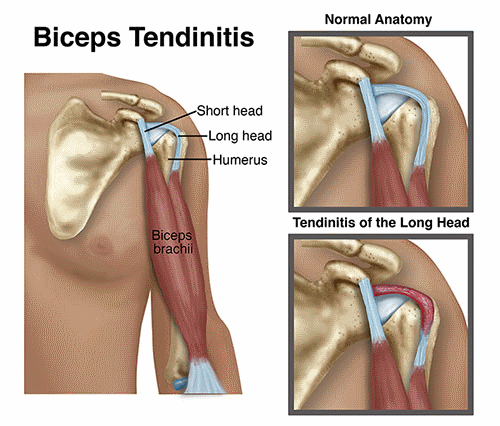

Biceps tendinitis is a common cause of shoulder pain, often developing in people who perform repetitive, overhead movements. Biceps tendinitis develops over time, with pain located at the front of the shoulder, and usually worsens with continued activity. When treating biceps tendinitis, physical therapists work to determine the exact source of the pain by assessing the entire shoulder, and typically prescribe a program of activity modification, stretching, and strengthening to resolve pain and return individuals to their desired activities.

What is Biceps Tendinitis?

The biceps muscle is made up of 2 parts: the long head and the short head. The long head of the biceps is most commonly implicated with tendinitis, as the tendon from the muscle runs up the length of the arm and attaches into the shoulder joint. It becomes a part of theshoulder joint capsule, which is surrounded by numerous other structures, including therotator cuff.

Biceps tendinitis result when excessive, abnormal forces are applied across the tendon, including tension (a pulling of the muscle and tendon), compression (pushing or pinching), or shearing (rubbing). When the tendon is subjected to repetitive stresses, it can become irritated, swollen, and painful.

There are many factors that may lead to biceps tendinitis, including:

- Activities requiring repetitive overhead movement of the arms

- Weakness in the rotator cuff and muscles of the upper back

- Shoulder joint and/or muscle tightness

- Poor body mechanics (how a person controls his or her body when moving)

- An abrupt increase in an exercise routine

- Age-related body changes

How Does it Feel?

With biceps tendinitis, you may experience:

- Sharp pain in the front of your shoulder when you reach overhead

- Tenderness to touch at the front of your shoulder

- Pain that may radiate toward the neck or down the front of the arm

- Dull, achy pain at the front of the shoulder, especially following activity

- Weakness felt around the shoulder joint, usually experienced when lifting or carrying objects or reaching overhead

- A sensation of "catching" or "clicking" in the front of the shoulder with movement

- Pain when throwing a ball

- Difficulty with daily activities, such as reaching behind your back to tuck in your shirt, or putting dishes away in an overhead cabinet

How Is It Diagnosed?

- When you first go to see your physical therapist, the therapist will review your medical history, ask you to describe your shoulder condition, and then perform a comprehensive physical exam of your shoulder. Your therapist will assess different measures, such as sensation, motion, strength, and flexibility, and may ask you to briefly perform the activities that cause your pain.

- Your physical therapist will likely touch various areas on your shoulder to see which seem to be most consistently painful. Other nearby areas, such as your neck and upper back, will also be examined to determine whether they might be contributing to your shoulder pain.

- Imaging techniques, such as x-ray or MRI, are typically not needed to diagnose biceps tendinitis. However, in the event that your physical therapist suspects there are other conditions present in your shoulder, you may be referred to an orthopedist for further investigation.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Once biceps tendinitis has been diagnosed, your physical therapist will work with you to develop an individualized plan tailored to your specific shoulder condition and your goals. There are many physical therapy treatments that have been shown to be very effective in treating this condition:

Range of Motion. Often, abnormal motion of the shoulder joint can lead to biceps tendinitis. Your physical therapist will assess your shoulder motion compared to the expected normal motion and to the motion of your other shoulder.

Strength. The muscles of the shoulder and upper back work together to allow for normal, coordinated upper-body motion. Based on the way the shoulder joint is designed (a ball-and-socket joint, like a golf ball on a golf tee), there are many directions in which the shoulder may move. Therefore, balanced strength of all the upper-body muscles is crucial to make sure the shoulder joint is protected and is moving efficiently. There are many exercises that can be done to strengthen the muscles around the shoulder so that each muscle is able to properly perform its job, and stresses are appropriately dispersed.

Manual therapy. Physical therapists are trained in manual (hands-on) therapy. Your physical therapist will gently move and mobilize your shoulder joint and surrounding muscles as needed to improve their motion, flexibility, and strength. These techniques can target areas that are difficult to treat on your own.

Pain Management. Your physical therapist may recommend therapeutic modalities, such as ice and heat, to aid in pain management.

Functional training. Whether you work in a factory, are a mother of a young child, or play baseball, the ways in which you perform your normal daily activities can affect the health of your muscles, tendons, and joints. Improper movements can, over time, cause pain in the body. Physical therapists are trained to be experts in assessing movement quality, and in training people to function at their best. Your physical therapist will be able to point out and correct faulty movements, so you are able to attain and maintain a pain-free shoulder. Often, the strategies learned through specific education from your physical therapist will allow you to avoid reversing the positive effects of your physical therapy treatment during your normal daily activities, and help make sure your improvements last.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

Fortunately, there is much that can be done to prevent biceps tendinitis. Some general tips include:

- Avoid repetitive overhead activities that cause shoulder pain. If you must move this way for your job or sport, make sure you set aside time to properly rest your shoulder, to avoid overworking it.

- Check your posture. The shoulder, neck, and back are all at risk of injury when they are held in a poor posture over a long period of time. Ask your physical therapist to discuss your work environment; describe how you move (or don't move) throughout the day.

- Avoid lifting or carrying heavy objects held away from your body. Keep items close to the body and, when possible, use both hands and arms.

- Perform rotator-cuff strengthening exercises regularly.

- Consult with a physical therapist if your symptoms are worsening despite rest.

What is a Biceps Tendon Rupture?

The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint made up of 3 bones: the upper-arm bone (humerus), the shoulder blade (scapula), and the collar bone (clavicle). The ball at the top of the upper-arm bone is called the head of the humerus. The socket on the shoulder blade is called the glenoid fossa. A tendon is a fibrous bundle that attaches a muscle to a bone. The muscles and tendons of the rotator cuff hold the ball into the socket of the shoulder. The biceps muscle has 2 tendons that attach it to the shoulder and travel the length of the upper arm and insert just below the elbow. The biceps muscle is responsible for bending (flexing) the elbow and rotating the forearm. One of the tendons is called the "long head" of the biceps muscle; it attaches to the upper-arm bone. The second area of attachment is called the "short head" of the biceps; it attaches the muscle to a bony bump on the shoulder blade called the coracoid process.

Most commonly, the biceps tendon will tear at the long head of the biceps at the upper-arm bone, leaving the second attachment at the shoulder blade intact. The arm can still be used after this type of rupture, yet weakness will be present in the shoulder and upper arm. A tear can either be partial, when part of the tendon remains intact and only a portion is torn away from the bone, or complete, where the entire tendon is torn away from the bone.

A biceps tendon rupture occurs when the biceps muscle is torn from the bone at the point of attachment (tendon) to the shoulder or elbow. Most commonly, the biceps tendon is torn at the shoulder. These tears occur in men more than women; most injuries occur at 40 to 60 years of age due to chronic wear of the biceps tendon. In younger individuals, the tear is usually the result of trauma (such as an auto accident or fall). Biceps tendon ruptures can also occur at any age in individuals who perform repetitive overhead lifting or work in occupations that require heavy lifting, and in athletes who lift weights or participate in aggressive contact sports.

How Does it Feel?

After sustaining a biceps tendon rupture, you may experience:

- Sharp pain in the upper arm or elbow

- Hearing a "pop" or snap at the shoulder or elbow

- Bruising and swelling in the upper arm to elbow

- Weakness in the arm when bending the elbow, rotating the forearm, or lifting the arm overhead

- Tenderness in the shoulder or elbow

- Muscle spasms in the shoulder and arm

- A bulge or deformity in the lower part of the upper arm (a "Popeye arm")

How Is It Diagnosed?

- In most cases, a thorough history and physical examination of the involved arm can diagnose a biceps tendon rupture. Your physical therapist will ask you several questions regarding your medical history, your regular daily tasks at home and at work, and your recreational or sports activities. Your physical therapist will ask how the injury happened and where you are having pain and/or weakness.

- Your physical therapist will examine your entire upper arm for bruising or swelling, and gently touch it to determine if there is any tenderness over the biceps region at the shoulder, upper arm, or elbow. Your physical therapist also will examine the amount of motion and strength present on the involved side in the shoulder, forearm, and elbow, compared to the noninvolved side. Functional testing may also be performed to determine what daily tasks are difficult for you to perform (eg, lifting an object, reaching overhead, reaching behind the body, or rotating the forearm to open a door).

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

A biceps tendon rupture often is treated without surgery. Your physical therapist will design an individualized treatment program to help heal your injury in the safest and most efficient way possible. Treatment may include:

Rest. You will be instructed in ways that allows the limb to rest to promote healing.

Icing. Your physical therapist will show you how to apply ice to the affected area to manage pain and swelling.

Range-of-Motion Activities. Your physical therapist will teach you gentle mobility exercises for the shoulder, elbow, and forearm, so your arm does not get stiff during the healing process.

Strengthening Exercises. As the pain and swelling ease, gentle strengthening exercises with resistant bands or light weights will be added.

Functional Activities. You will learn exercises to help you return to the activities you performed before the injury.

Education. Your physical therapist will teach you how to protect your joints from further injury. You will learn how to properly lift objects once the arm is healed, and how to avoid lifting objects that are simply too heavy.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

To prevent a biceps tendon rupture, individuals should:

- Maintain proper strength in the shoulder, elbow, and forearm.

- Avoid repetitive overhead lifting and general overuse of the shoulder, such as performing forceful pushing or pulling activities, or lifting objects that are simply too heavy. Lifting more than 150 pounds can be dangerous for older adults.

- Use special care when performing activities, such as lowering a heavy item to the ground.

- Avoid smoking; it introduces carbon monoxide into the body and leaves less oxygen for the muscles to grow and heal.

- Avoid steroid use, as it weakens muscles and tendons.